Building Caring, Trusting Relationships in a Remote Learning World (Pt. 1)

Building relationships with students through screens is as challenging as it sounds. Here's what we've learned so far from our schools across the country.

A 4-PART SERIES ON DEVELOPING CARING AND TRUSTING RELATIONSHIPS WITH STUDENTS WHILE SCHOOLS ARE CLOSED (PT. I)

We’re a month into remote learning. By now, you may have re-established routines and rituals with your students, but how are you addressing the inimitable loss of human connection—the welcome fistbumps at the door; the familiar buzz of engagement when students make meaning; the advice session over lunch with a student who needed extra support?

Some of your students may even be experiencing anticipatory loss, a form of grief that stems from feelings of uncertainty about the future. Other students may still be trying to navigate learning at home where they don’t have access to quiet learning spaces or consistent WiFi. Still, others may be supporting parents who work, with increased responsibilities around the house, and some students are even learning to cope in unstable or toxic environments.

As we transition to remote learning, we’re learning that caring, trusting relationships are essential and crucial for students to thrive, especially for students now learning how to adapt to and become pioneers of a new, rapidly changing world.

In this four-part series, we’ll explore themes that help us understand how to build powerful connections for learning to meet students who are most vulnerable to falling behind, with evidence-based practices. These insights come from our discussions with XQ schools across the country, and we wanted to share!

This week, we’ll focus on developing systems and structures for learners to connect and build strong relationships with adults from their school in remote learning environments. We’ll answer:

- What structures and protocols can we establish so that every learner is well-known by at least one adult in the school?

- How do we create synchronous and asynchronous schedules so that we can set consistent and clear expectations that students are valued as learners?

- And how do we ensure our complex learners receive critical, timely support?

Let’s dive in.

What structures and protocols can we establish so that every learner is well-known by at least one adult in the school?

Across the country, educators are prioritizing their relationships with students by creating intentional time for students to check-in with designated adults in the school. By ensuring that at least one adult has a positive relationship with a student through strategies like virtual relationship mapping, students are more likely to have academic success, reduced absenteeism, increased motivation and engagement, and reduced emotional distress.

One way schools are doing this is through adapted advisory structures; a powerful, yet flexible way to foster school culture and create safe, vulnerable environments for students to make their voice heard. By providing dedicated spaces and times for informal connection, students can name, process, and accept what may be a steady stream of new thoughts and feelings in the midst of crisis, while also providing a consistent community space for connection and collaboration between students.

“It’s brought us so much closer together,” says Vera Brown, a 10th grade student at Crosstown High. “It makes me so happy to just be able to talk about my life and check in to see how my peers and advisors’ lives are going right now.”

Currently, Crosstown’s virtual advisory structure meets three times a week. They’ve adapted their structure to be especially responsive to a transition to remote learning. “If a student misses more than two sessions in a row, we’re following up to see what is happening,” said Chris Terrill, Executive Director of Crosstown High. “If a kid is not connecting, then we’re connecting.”

Similarly, school leaders at Latitude High School, in Oakland, California, have devised a designated “parent call” team to follow-up with students and families, if there is disengagement from a student. When a student is absent from a session, instead of just logging into a tracker, the teacher drops a note in our #studentattendance channel so we can let everyone know at once. This allows Latitude’s standby team to responsively call the family to support, whether that’s helping them secure internet connection or finding accommodations when a student is taking care of a sibling.

At Brooklyn Laboratory High School in New York City, over one-third of students qualify for special education services, so the role of Deans have shifted to what they refer to as “Chief Engagement Agents.” These agents strategically monitor attendance, engagement, and build meaningful touchpoints for students and their families.

Lastly, we’re finding that added responsibility of taking on the roles of social worker, counselor, and mentor may heighten teachers’ own stress levels and secondary psychological trauma. Our school leaders are also reaching out to teachers and staff in their school ecosystem for regular check-ins. Principal Lillian Hsu of Latitude High reminds her staff in daily meetings that, “If there’s something that’s important to you, don’t hesitate to pick up the phone. We’re all figuring this out together.”

How do we create synchronous and asynchronous schedules in order to set consistent and clear expectations for student learning?

Most educators know that when the brain is stressed, the ever-planner prefrontal cortex shuts down immediately. The amygdala, your brain’s integrative center for emotions, has essentially ‘hijacked’ the brain, flooding your body with cortisol signals, which prevent novel information for learning to be absorbed.

However, routine, ritual, and clear expectations for learning—like school schedules and timelines for assignment and project completion—can generate a feeling of predictability and stability by significantly lowering the cognitive load of things that students need to plan and manage. This stability signals to your students’ brains: ‘There is order.’ And within these structures, students have control and freedom for higher-order thinking, like creating, building, and designing.

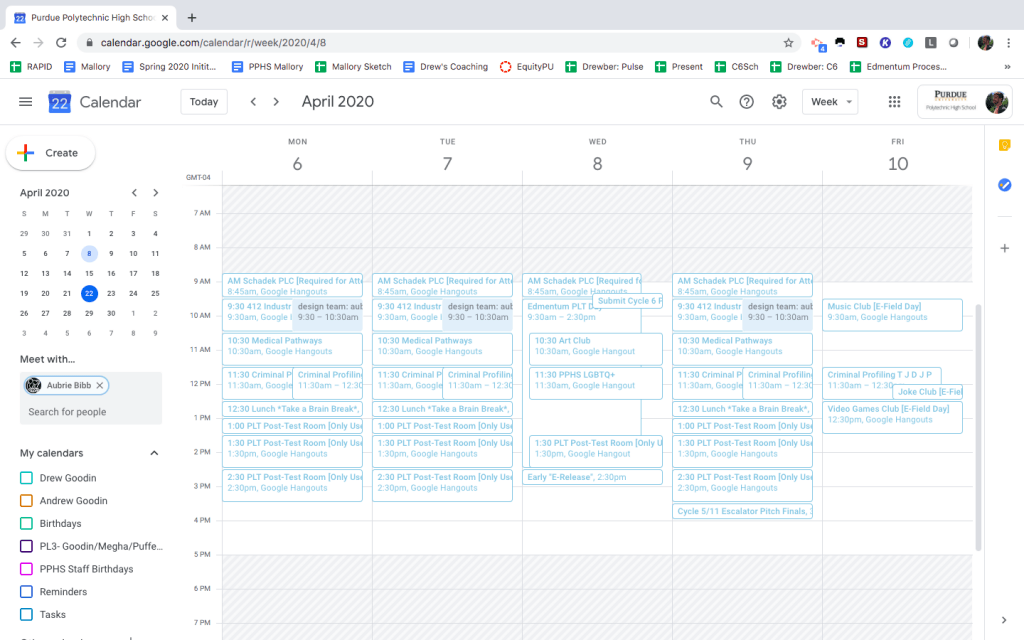

Purdue Polytechnic High School in Indianapolis, Indiana, focuses on preparing students to solve complex problems with industry-generated projects that lend to a design thinking approach. They were one of the lucky schools that was already well-integrated with technology and so were prepared for a transition to remote learning. Their existing projects seamlessly moved to online, while virtually continuing their students’ check-in’s with coaches on a daily basis.

But remember, a one size fits all schedule has never worked, so why should it work for a remote learning environment? One student at Purdue Polytechnic High School (PPHS), for example, was responsible for watching three kids at home while parents were working. His teacher, or ‘coach’ as they are called at PPHS, was able to schedule a check-in during the evenings to ensure he was meeting this students’ unique learning needs.

At the same time, don’t be afraid to get it wrong the first time: after learning that students needed more live support beyond asynchronous daily assignments, teachers at Brooklyn Laboratory and Washington Leadership Academy set up office hours for each subject so students can ask questions that might simultaneously help their peers. And at Latitude High School, teachers set up multiple focus groups with students to try to learn what assignments presented a hardship and what processes were working about the schedule. These meetings allowed educators to listen to their students’ needs and responsively adapt.

And with just over a month left in the school year, we’re finding that our schools are starting to think about their schedules in time-based phases. While learning scientists have long known that chunking is beneficial to memory, psychologists are also recommending to chunk your quarantine life strategically in order to calm overwhelming feelings.

So ask yourself: what do your students need to know to be successful in the next two weeks? What about the next two months? And the next two years? How can you help structure expectations around students learning now so that they can grow to reach their ambitious, long-term goals?

How do we ensure that our complex learners receive critical, timely support?

Students who already struggle with time management, goal-setting, prioritizing, problem-solving, and other executive functioning skills, or students who require additional services, like 504 plans, IEP’s and other special services, are especially vulnerable to falling behind, even if remote learning is achieved perfectly.

But “saying, ‘We don’t know how,’ or ‘We can’t do this’ is not an acceptable response” to the education of complex learners, says Erin Mote, Executive Director of InnovateEDU and co-founder of Brooklyn Laboratory. In response to COVID-19, Brooklyn Laboratory has launched Educating All Learners, with an alliance of technology and inclusive education partners to provide quality and practical solutions for serving complex learners in an era of remote instruction. In one week alone, they’ve launched 5 webinars for educators, covering topics like supporting students with IEP’s, virtual learning strategies for dyslexia, moving speech therapy online, and office hours with renowned experts in cognitive and emotional differences in youth.

Brooklyn Laboratory is also providing critical support to learners by tracking the engagement of their students through a multi-tiered system of support. Based on progression, students may move between tiers, if advisors find that they are becoming more engaged and able to learn independently. The most intensive ‘Tier 1’, for example, specifies regular connection points that allow advisors to connect with learners around reading interventions, counseling, co-teaching supports, and more.

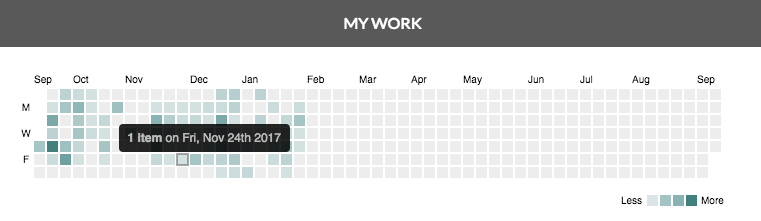

In speaking to other schools in our network, we have also found that our most vulnerable learners already greatly benefit from flexible scheduling models. For example, at Da Vinci Rise High educators have an internal learning management system that already tracks engagement from students based on logins and project submissions. They’ve engineered this system to act as a custom-made “work journal” that also allows the team to track time spent on independent learning as well.

Don’t forget to keep flexing to your students’ needs with multiple modalities to address the needs of your most diverse learners, including students with disabilities and students who are English language learners. Educators like Lauren Murray, English teacher at RISE, are also continuing to realize the importance of finding multiple ways to meet students where they are: “I screen cast, provide audio, and video, so that they have multiple ways for understanding,” she says.

Lastly, our partners at Marshall Street, Summit Public School’s R&D arm, have curated a sequence of best practice lists to address learner variability, including ways to create accessible virtual learning environments, guidance for small group instruction and running virtual IEP meetings, and a running log accommodations and best practices that can easily transfer to the virtual setting.

Conclusion

We think this is a pivotal moment for educators to keep on doing, at the heart and core, what they wanted to do before: create engaging, meaningful learning experiences. The transition to remote learning—while a roadblock—asks us to find new, innovative ways to create these meaningful experiences and forces us to recognize the individual needs required to get each student to reach their highest potentials. We hope you will be able to apply some of these systems and structures to connect and build strong relationships with students in your own remote learning environments.

We’ll leave you with these wise words from Crosstown High’s Chris Terill:

“Teachers and administrators… In this time of crisis, content is less important than the mental well-being of our students. Use this time as an opportunity to connect with students on a more personal level. There is usually not enough time in the day. We now have the time.”